[Note: This article uses the original spelling of Sand Point as two words instead of the current single word.]

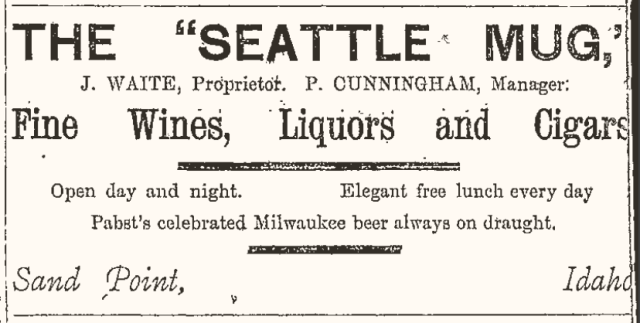

Sand Point had a bit of a reputation in its youth, but even by the town’s questionable standards, the riot at the Seattle Mug saloon was a doozy.

Or was it?

In mid-February 1892, a dispatch from Spokane told of the terrible brawl at the opening of Sand Point’s new Seattle Mug saloon. The crowd included 300 “railroaders, cow punchers and mining men” as well as 27 of “the lowest women in the northwest.” Things soon degenerated into “bloodshed and riot.” A character known as Cucumber Pete started a fight and was shot by another man. Two of the women, Irish Mollie and Iolanthe, were wounded, perhaps mortally, and “Steamboat Johnny had his brains blown out.” Fortunately the US Marshal and Sheriff arrived with deputies to stop the mayhem and lock up more than two dozen of the “worst characters in the west.”

Newspaper editors could not resist this Wild West story. Within a few days, it appeared in dozens of papers all across the United States and into Canada, from Albuquerque and Macon to St. Louis and Buffalo and up to Montreal. While some newspapers omitted the mention of lowlife women, the story remained essentially the same, with occasional variations. The Potter Enterprise in Coudersport, Pennsylvania, evidently was unfamiliar with the term “cow punchers” and changed the fight participants to mining men and “cow purchasers,” leaving the railroaders out entirely.

The sensational story raised the hackles of the editor of Sand Point’s Pend d’Oreille News. After quoting the dispatch as it appeared in the Helena Independent-Record, he wrote, “…it is an outrage that some obscure correspondent for a great daily paper can, without any [facts], send over the wires such a ridiculously blood-curdling dispatch as the above. There ought to be a remedy.” He added that such stories take up space to the detriment of legitimate news. A few days later, the Helena paper noted that J. L. Prichard, Justice of the Peace at Sand Point, denied that there had been any shootings or trouble of any kind.

The editor of the Spokane Falls Review also came to the defense of Sand Point. “It is a little strange that neither the people nor the authorities of Sand Point have heard of any such calamity,” he noted. “The only basis for such a report … was the opening of a dance house on the flats, with the usual drinking and noise which accompany such events, but nothing further of serious import.”

The Review editor, however, was less concerned about Sand Point’s reputation than that of his own town, which appeared in the dateline of every one of the dozens of lurid stories smeared across the country. He blamed a “youth” working for “the bogus paper of this city” for the original dispatch, evidently not the first time this had happened. Such stories, he complained, were “calculated to place Spokane in the light of being the center of all of the lawlessness and immorality of the northwest.” He dismissed the Seattle Mug story as “a small scuffle [which] took place in a dancehouse at Sand Point; no one was seriously hurt, and the affair was all over in five minutes.”

So was there any basis for the story of the Seattle Mug riot?

During late 1891 and early 1892, Sand Point was humming with activity. The Great Northern Railway was laying its tracks westward from Kalispell toward Sandpoint. To speed construction, GN had a spur built from the Northern Pacific line in Sand Point, running about a mile and a half west to the new railroad right-of-way, close to where Baldy Road crosses the tracks today. Hundreds of railroad cars carried rails, plates, and spikes on the spur, enabling crews to lay tracks both eastward toward Kalispell and westward toward Albeni Falls. This project brought large numbers of men to Sand Point for work. Paychecks often didn’t last long, squandered on booze, gambling, and women, all of which led to frequent fights with the resulting black eyes and bloody noses. There were some prospectors in the area and lots of railroad workers. But cow punchers—or cow purchasers? No way.

Even Sand Point boosters, like J. R. Law, acknowledged the rougher side of town. He pointed out that saloons and gambling were common anywhere there was a large payroll like that of the Great Northern. “It is not a genteel business,” he said, “and rough and ill-mannered men can always be found among those who follow railroad construction.” The editor of the Pend d’Oreille News defended Sand Point as “one of the most orderly towns in the northwest.” He attributed the bad reputation to outsiders who misunderstood the amount of business being done in town, where large sums of money were exchanged. The booming economy gave uninformed visitors the impression that the town was “wild and wooly” when this was normal for the headquarters of railroad construction.

The Missoula Weekly Gazette obviously did not believe the sensational story of the riot, and, tongue in cheek, wrote of “the blood and gore, black eyes, broken noses and the usual et ceteras.” It went on to say that Cucumber Bill (not Pete) whipped his opponents in eleven fights and wanted to make it an even dozen. Alas, he met his match, and “‘Cucumber’ became a pickle.”

The Seattle Mug saloon was again in the news just a month after the earlier story. This time, Thomas Meagher, better known as Steamboat Tommy, got drunk and picked a fight. Patrick Cunningham, manager of the bar, shot him in what he and other witnesses claimed was self-defense. Tommy had gotten his moniker from his years of working on Coeur d’Alene steamboats. One account of his death claimed that he was working at the Seattle Mug as a “chippy herder,” one who managed the women who worked there. He was known to be rough with women and feared by many.

Track laying on the Great Northern proceeded rapidly and Sand Point soon emptied when the laborers moved on down the line. With business dependent on large numbers of men, flush with money, the Seattle Mug folded by June 1892, just four months after opening.

The rough board building, located on the flats in the vicinity of today’s city beach, did not stand empty for long. After losing his livery stable to fire in early June, Harry Baldwin converted the Seattle Mug into a barn, enabling him to continue his business while he rebuilt. His new building was ready by late August and the Seattle Mug was once again left vacant, its past, notorious or not, quickly forgotten.

Sources:

“Seattle Mug” Opening, Marion (IN) Chronicle Tribune, 18 February 1892, 3:5; No title, Anaconda Standard, 22 March 1891, 10:2; Thriving Idaho Towns, Helena Independent-Record, 4 May 1891, 1:1-2; President Hill Going West, Helena Independent-Record, 11 November 1891, 4:3; Railroad Work, Missoula Weekly Gazette, 16 December 1891, 3:4; No title, Pend d’Oreille News, 13 February 1892, 5:3; Bloodshed in a Dance Hall, Las Vegas (NM) Daily Optic, 17 February 1892, 5:1-2; Lively Idaho Town, Buffalo (NY) Enquier, 17 February 1892, 1:6; Riot and Bloodsheed [sic] in Idaho, Carrol (IA) Sentinel, 17 February 1892, 2:1; Riot and Bloodsheed [sic] in Idaho, Lincoln (NE) Journal Star, 17 February 1892, 2:7; St. Louis (MO) Globe-Democrat, 17 February 1892, 3:2; A Word From Sand Point, Spokane Falls Review, 18 February 1892, 10:5-6; A Dance House Riot, Chippewa Falls (WI) Herald-Telegram, 18 February 1892, 1:4; Riot And Bloodshed, Columbus (NE) Telegram, 18 February 1892, 1:2; A Lively Opening, Albuquerque Journal, 18 February 1892, 1:7; How It Was Dedicated, Anaconda Standard, 18 February 1892, 1:3; A Northwestern Riot, Macon (GA) Telegraph, 18 February 1892, 1:6; A Wild West Scene, Knoxville (TN) Journal and Tribune, 18 February 1892, 1:6; A Spokane Society Event, Montreal (Quebec) Gazette, 18 February 1892, 8:5; “Seattle Mug” Opening, Clarksville (TN) Leaf-Chronicle, 19 February 1892, 8:1; Spokane In A Lurid Light, Spokane Falls Review, 19 February 1892, 6:3; No title, Pend d’Oreille News, 20 February 1892, 4:1; “Seattle Mug” Opening, Pensacola (FL) News, 20 February 1892, 1:6; The Sand Point Music Hall Opening, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 20 February 1892, 2:2; No title, Helena Independent-Record, 21 February 1892, 8:3; Sand Point Items, Spokane Falls Review, 21 February 1892, 2:5; No title, Helena Independent-Record, 21 February 1892, 8:3; No title, Missoula Weekly Gazette, 24 February 1892, 4:5; In the Northwest, Coudersport (PA) Potter Enterprise, 24 February 1892, 2:2; No title, Prescott (AZ) Weekly Journal-Miner, 24 February 1892, 2:1; A Dance House Row, Bismarck (ND) Weekly Tribune, 26 February 1892, 2:5; Shreveport (LA) Times, 25 February 1892, 6:3; Sioux City (IA) Journal, 19 February 1892, 1:4; St. Paul (MN) Globe, 18 February 1892, 7:2; St. Albans (VT) Daily Messenger, 18 February 1892, 1:5; Murder At Sand Point, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 15 March 1892, 1:6; Killed in a Dance Hall, Pend d’Oreille News, 19 March 1892, 4:1; Condensed News, Missoula Weekly Gazette, 23 March 1892, 5:4; The “Seattle Mug,” Missoula Weekly Gazette, 23 March 1892, part 2, 1:5; Business and Pleasure, Missoula Weekly Gazette, 30 March 1892. 1:6; Ad, Pend d’Oreille News, 23 April 1892, 5:4-5; Disastrous Conflagration, Pend d’Oreille News, 11 June 1892, 5:1; Local and Personal, Pend d’Oreille News, 25 June 1892, 5:3; Local and Personal, Pend d’Oreille News, 20 August 1892, 5:3.

My comment would not post, but just had to relay that the piece was funny and appreciated! Marilee Wein

LikeLike

Thanks, Marilee! I had fun with this crazy story. As you know, history is far from boring. And your comment did post after all. Cheers!

LikeLike